Hammerbeam roof

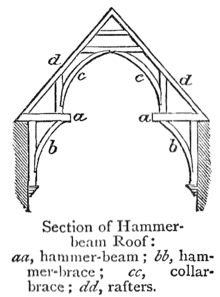

A hammerbeam roof is a decorative, open timber roof truss typical of English Gothic architecture and has been called "the most spectacular endeavour of the English Medieval carpenter".[1] They are traditionally timber framed, using short beams projecting from the wall on which the rafters land, essentially a tie beam which has the middle cut out. These short beams are called hammer-beams[2] and give this truss its name. A hammerbeam roof can have a single, double or false hammerbeam truss.

Design

[edit]A hammer-beam is a form of timber roof truss, allowing a hammerbeam roof to span greater than the length of any individual piece of timber. In place of a normal tie beam spanning the entire width of the roof, short beams – the hammer beams – are supported by curved braces from the wall, and hammer posts or arch-braces are built on top to support the rafters and typically a collar beam. The hammerbeam truss exerts considerable thrust on the walls or posts that support it.[3] Hammerbeam roofs can be highly decorated including ornamented pendants and corbels, with church roofs often including carved angels.

A roof with one pair of hammer beams is a single hammerbeam roof. Some roofs have a second pair of hammer beams and are called double hammerbeam roofs (truss).

A false hammerbeam roof (truss) has two definitions:

- There is no hammer post on the hammer beam[4][5] as sometimes found in a type of arch-brace truss;[6] or

- The hammer beam joins into the hammer post, instead of the hammer post landing on the hammer beam.[7]

Examples

[edit]

Possibly the earliest hammer-beamed building still standing in England, built in about 1310 [8] and located in Winchester Cathedral Close, is the Pilgrims' Hall, now part of The Pilgrims' School.

The roof of Westminster Hall, which underwent renovation from 1395 to 1399, is a fine example of a hammerbeam roof. The span of Westminster Hall is 20.8 metres (68 ft. 4 in.), and the opening between the ends of the hammer beams 7.77 metres (25 ft. 6 in). The height from the paving of the hall to the hammerbeam is 12.19 m (40 ft.), and to the underside of the collar beam 19.35 metres (63 ft. 6 in.), so that an additional height in the centre of 7.16 m (23 ft. 6 in.) has been gained. In order to give greater strength to the framing, a large arched piece of timber is carried across the hall, rising from the bottom of the wall piece to the centre of the collar beam, the latter also supported by curved braces rising from the end of the hammerbeam.[9]

Other important examples of hammerbeam roofs exist over the halls of Hampton Court and Eltham palaces, and Burghley House near Stamford. There are also numerous examples of smaller dimensions in churches throughout England, particularly in the eastern counties. The ends of the hammerbeams are usually decorated with winged angels holding shields; the curved braces and beams are richly moulded, and the spandrels in the larger examples filled in with tracery, as can be seen in Westminster Hall. Sometimes, but rarely, the collar beam is similarly treated, or cut through and supported by additional curved braces, as in the hall of the Middle Temple, London.[9]

Recently, as part of an extensive restoration project undertaken by Historic Scotland, the hammerbeam roof of the Great Hall at Stirling Castle was completely restored. Green oak from 350 Perthshire trees was used to fabricate and erect 57 hammerbeam trusses spanning approximately 15 metres. Since its construction around 1502 by King James IV of Scotland, structural loads from the roof had caused the walls of the hall to deflect outwards. To ensure that the ridge of the roof would be level and straight, the trusses were each made with a slightly different pitch and span. The restoration started in 1991 and was completed in 1999.[10]

Other examples are in the Parliament Hall in Edinburgh, the Great Hall in Edinburgh Castle, the chapel of New College, Oxford, the Great Hall of Athelhampton House, Dorchester, Dorset the Great Hall of Darnaway Castle in Moray, and the Great Hall of Dartington Hall, Totnes.

A spectacular modern example of a hammer-beam roof is the new Gothic roof of St George's Hall at Windsor Castle, designed by Giles Downe and completed in 1997. This replaced the previous flatter roof which was destroyed in the 1992 Windsor Castle fire.

It is incorrectly believed by some that the widest hammerbeam roof in England at 72 ft (22 m) wide is in the train shed at Bristol Temple Meads railway station by Isambard Kingdom Brunel .[11] In fact, the station roof uses modern cantilever construction; the hammerbeam style elements are purely decorative. The hammer posts and brackets support nothing, as all the weight of the roof is braced and supported by the massive side walls via the main timber ribs of the roof and the pillars inside the train shed.[12]

-

The restored new single hammerbeam roof in the Great Hall at Stirling Castle

-

Hammerbeam used inside a modern timber frame residence

-

Single hammerbeam ceiling, carved in oak by Patrick Keely at St. Mary – St. Catherine of Siena Parish, Charlestown, Massachusetts

-

A false hammerbeam roof in the Great Hall of Eltham Palace, England

-

The hammerbeam elements in Bristol's Temple Meads station are purely decorative, not structural.

-

A false hammer-beam roof in the Dictionary of French Architecture from the 11th to the 16th Century (1856) by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc

-

1870 arch-braced hammerbeam roof by Mallinson & Barber at the Church of St Thomas, Thurstonland, West Yorkshire

-

The ornamented pendants[13] in the Great Hall of the Wills Memorial Building (University of Bristol), completed in 1925, bombed in 1940 and restored in the 1960s

-

Hampton Court's ornate hammerbeam roof in the Great Hall

References

[edit]- ^ Bismanis, Maija R. The medieval English domestic timber roof: a handbook of types. New York u.a.: Lang, 1987. 163.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed.

- ^ Kidder, F. E. (1906). "21. The Hammer-Beam Truss". Building Construction And Superintendence. William T. Comstock.

- ^ Davies, Nikolas, and Erkki Jokiniemi. Dictionary of architecture and building construction. Amsterdam: Elsevier/Architectural Press, 2008. 144.

- ^ Alcock, N. W.. Recording timber-framed buildings: an illustrated glossary. London: Council for British Archaeology, 1989.

- ^ Sharpe, Geoffrey R.. Historic English churches a guide to their construction, design and features. London: I.B. Tauris, 2011. 111. fig. 61.

- ^ Wood, Margaret. The English Mediaeval House. London: Ferndale Editions, 1980, 1965. 319

- ^ Bullen, M., Crook, J., Hubbuck, R., and Pevsner, N., The Buildings of England: Hampshire: Winchester and the North. New Haven, Conn., and London: Yale University Press Pub., 2010. 621. ISBN 9780300120844.

- ^ a b One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Hammerbeam Roof". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 897.

- ^ "CTE - Great Timber Creations". cte.napier.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 9 April 2006. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ^ Burrough, THB (1970). Bristol. London: Studio Vista. ISBN 0-289-79804-3.

- ^ Buchanan, R. A.. Brunel: the life and times of Isambard Kingdom Brunel. London: Continuum, 2006. 74. ISBN 1852855258 states it is a "...mock-hammer-beam roof..."

- ^ Matthew Rice, Rice's Architectural Primer, Bloomsbury, 2009

Further reading

[edit]- Lynn Towery Courtenay, English Royal Carpentry in the Late Middle Ages: The Hammer-beam Roof. University of Wisconsin—Madison, 1979.

![The ornamented pendants[13] in the Great Hall of the Wills Memorial Building (University of Bristol), completed in 1925, bombed in 1940 and restored in the 1960s](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/3e/Hammerbeam_roof_in_the_Great_Hall_of_the_Wills_Memorial_Building.JPG/200px-Hammerbeam_roof_in_the_Great_Hall_of_the_Wills_Memorial_Building.JPG)